Erie’s early history is traditionally told as a story of Revolutionary War veterans and brave white pioneers carving frontier settlements out of the wilderness of northwestern Pennsylvania. Often missing from that narrative are the enslaved Africans brought here by their owners.

Lost on most of us in the 21st century is the fact that Pennsylvania, cradle of American freedom, even had slavery. In 1780, even as American colonists were locked in a bloody fight for independence, Pennsylvania became the first democratic body in world history to move toward gradual abolition of slavery. The law passed that year banned the importation of slaves and mandated that enslaved persons born before 1780 would remain so for life, while their children born after 1780 would remain “indentured servants” until the age of 28.

Among the prominent Erie citizens counting persons among their substantial property were Judah Colt, P.S.V. Hamot, Rufus Reed, and the Kelsos. When John Kelso died in 1821, the Erie press ran an advertisement selling “the time” of 18 year-old Bristo Logan. Following his purchase by John Cochran of Millcreek and ten additional years of enslavement, Logan married and ran his own ice cream business, pioneering a tradition of notable African American success in that enterprise.

One of the first white settlers in northwest Pennsylvania was John Grubb, who brought with him from Maryland a black man named Boe Bladen. Census records tell us that Grubb had several African Americans living in his household (likely Bladen and his sons), and we also know that Grubb moved at some point from enslaver to abolitionist. Originally taken from Guinea, west Africa, Bladen arrived with striking marks on his body. Conflicting accounts hold that the markings were indicators either of his tribal identity or savage treatment by a previous owner.

Sometime around the turn of the century Bladen purchased a 400-acre tract of land in Millcreek Township from the Pennsylvania Population Company. Though reduced somewhat in size over time, the Bladen Farm (marked on the landscape today only by the “Bladen Road” street sign) remained the property of three generations of Bladens for a full century. How Boe Bladen was able to purchase the land, and how and when he earned his freedom remains murky, but John Grubb almost certainly played a role in helping the man become one of the first–and, if we include his sons, longest-tenured–landowners in early Erie County history.

By the early nineteenth century, Harborcreek Township was home to the largest population of enslaved and free African Americans in northwest Pennsylvania. Robert McConnell and James Titus were first to arrive, brought here as young children by early settler Thomas Rees. It is quite possible that at least Spanish American War veteran Robert McConnell, buried alongside Rees in Gospel Hill Cemetery and described in early Erie histories as a “mulatto,” was Rees’s son. Upon their 28th birthday, Rees granted McConnell and Titus 50 acres each.

These are just a few of the African Americans from Erie’s early history whose lives remain etched in relative obscurity but who doubtlessly contributed to the growth of the larger community. Indeed, the burgeoning maritime and industrial powerhouse that Erie County became by the mid-19th century was built partly with the toil of enslaved and free black men, women and children.

That truth was reinforced during the summer of 1813 when the county’s still small black population (likely no more than 50) more than doubled with the arrival of African American sailors from the eastern seaboard. Many of them skilled and experienced sailors, African American seamen—who in this era enjoyed a greater measure of respect and equal treatment on board a ship than black men generally received anywhere on land—made up roughly a quarter of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s force that defeated and captured a British naval squadron in the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813. Following the dramatic U.S. naval victory, the fleet’s commanding officer noted that Perry spoke “highly of the bravery and good conduct of the negroes, who formed a considerable part of his crew. They seemed to be absolutely insensible to danger.”

On land, the struggle for what Abraham Lincoln would call a “new birth of freedom” at Gettysburg intensified in the years leading to the Civil War. Erie had a chapter of the white-dominated American Colonization Society that promoted a “back to Africa” movement, but most patriots who believed a better future possible for African Americans focused their energies in anti-slavery work, some as bravely outspoken members of the Anti-Slavery Society.

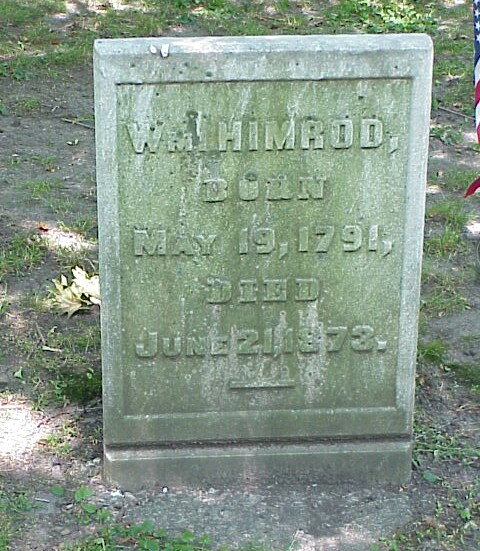

In Erie, William Himrod, a pioneer of the city’s renown iron industry and an outspoken abolitionist, used his home at Second and French Streets to house the “Sabbath School for Colored Children.” Himrod then established the community of “New Jerusalem” north of Sixth and west of Sassafras to Cherry Street for free blacks and destitute whites, selling lots at affordable prices with the requirement that they build a home and help forge an interracial community.

The Jerusalem appellation stuck, in part because of the pilgrimage-like journey from the city across a yawning wooded ravine in those years. Over time, Jerusalem became home to many prominent black residents and institutions. Looking north, the community faced Presque Isle Bay and the promised land of Canada; to the south soon would be “Millionaire’s Row,” a prominent stretch of grand mansions housing the richest and most prominent Erie industrialists, shipping magnates, financiers, and political elites.

More widely celebrated than these community-building efforts is Erie’s association with the Underground Railroad (UGRR)—neither a railroad nor underground, but a complex chain of homes, churches and countless other places of refuge extending from the Deep South to northern locales like Erie and Canada in the decades leading to Civil War. Much Underground Railroad history in Erie County remains shrouded in legend—unsubstantiated fables of underground tunnels extending into Presque Isle Bay, for example. By the very nature of what was a criminal enterprise carried out in secret, a lack of documentation has long frustrated historians.

We know for certain, however, that for reasons owing to its location at the southern edge of narrow Lake Erie just across from Long Point, Ontario, northwest Pennsylvania was a region of vigorous UGRR activity by black and white residents. From the late 1820s through the Civil War, Erie citizens helped many of the hundreds of slaves a year who managed to escape to their freedom on the Underground Railroad.

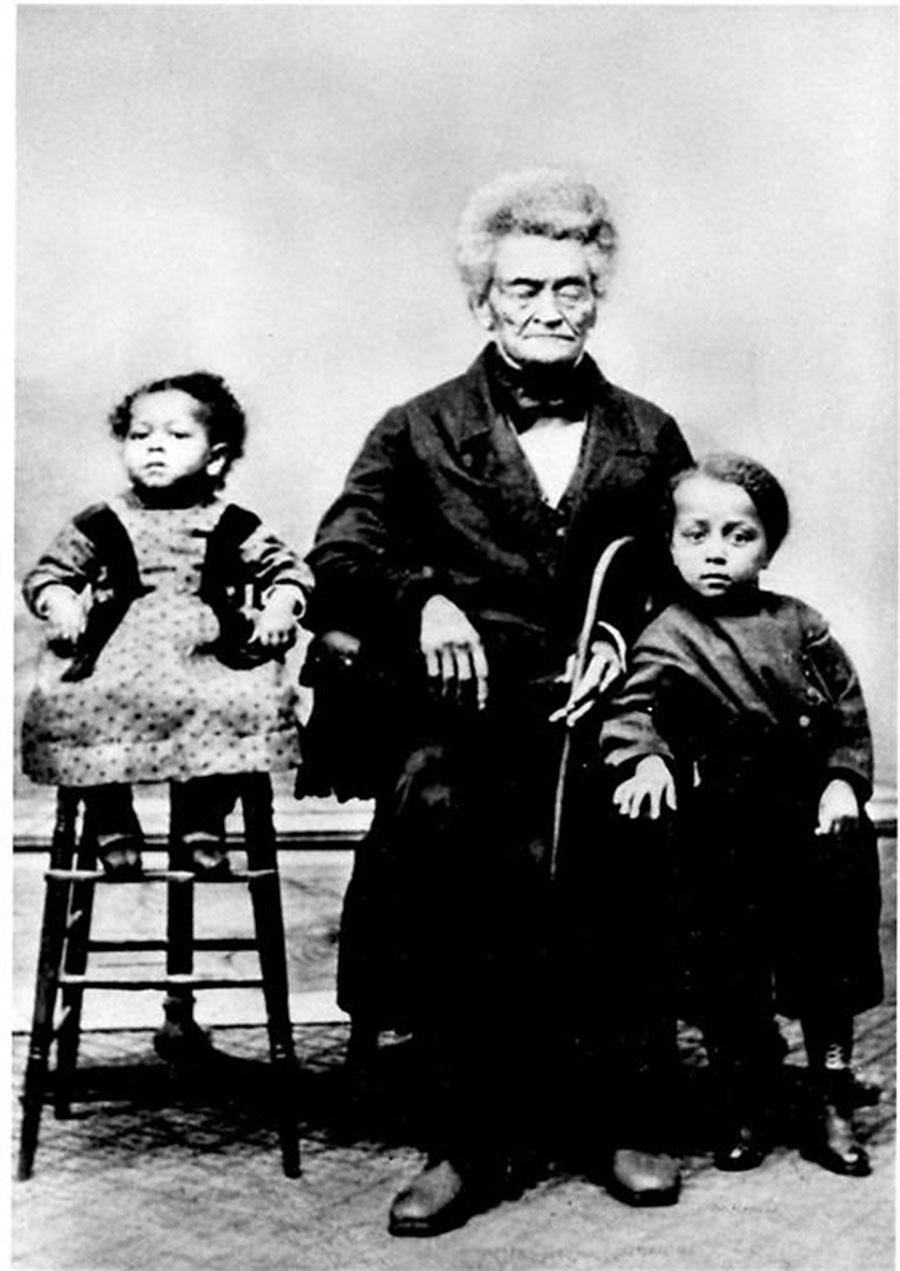

We know of Albert and Robert Vosburgh, father-and-son barbers who for many years used their shop at 314 French Street to harbor, re-groom, and outfit anew runaway enslaved persons who would then move by night northeastward along the edge of the shoreline, or across Lake Erie to Canada. Indispensable to their work was Hamilton E. Waters, (maternal grandfather of world-famous musician Harry T. Burleigh), hired by Albert Vosburgh to clean and press clothes—and also to surreptitiously help direct fugitives toward their freedom. Refuge in Canada was essential after the passage in 1850 of the Fugitive Slave Act, which heightened the fear and resentment of slave catchers who roamed the region.

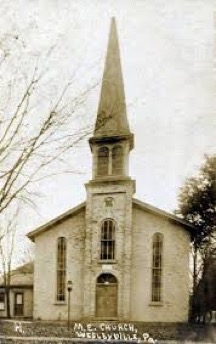

We know of local Underground Railroad conductor Frank Henry, who hid persons seeking freedom in the Wesleyville Methodist Church. Henry often received them from Hamilton Waters, who directed their clandestine route eastward out of Erie to the shoreline at Four Mile Creek. At the west end of the county was conductor Reverend Charles Shipman of the Universalist Church in Girard. An outspoken abolitionist, Shipman received and gave sanctuary to fugitives coming from the south, redirecting them either west toward the Ohio border or eastward to Erie and Harborcreek.

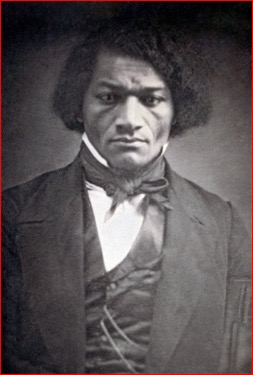

The cause of abolition was bolstered by the True American, a newspaper published by Henry Catlin from the second floor of the Lowry Building at East Fifth and French. For years, runaway enslaved persons were hidden from slave-catchers in the newspaper bins of Catlin’s office. It was Catlin who on April 24, 1858 brought to Erie the nation’s most eloquent anti-slavery voice, Frederick Douglass. In the face of an angry mob that nearly ran Catlin and Douglass out of town, the great orator delivered his lecture that evening at Park Hall carrying the title, “Unity of the Human Race.”

6. Harry Thacker Burleigh, Hamilton Waters, Reginald Burleigh (L-R)

7. Wesleyville Methodist Episcopal Church

8. Frederick Douglass, ca. 1850

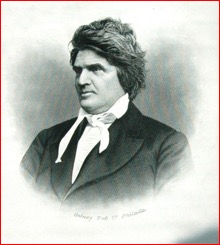

The Lowry Building that housed The True American belonged to state Senator Morrow Barr Lowry, in the Civil War era one of Erie’s most successful businessmen, but far more than that. Remembered as the “Moral Conscience” of the senate, Lowry advocated abolition in the state legislature, as well as debt forgiveness for the poor. An acquaintance of John Brown, Lowry visited the radical abolitionist in Charles Town, Virginia while he awaited execution for the 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry that helped trigger the Civil War. When war came, Lowry contributed $2,000 toward the fabled 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry that would fight at Gettysburg under the command of Colonel Strong Vincent, and also pushed for arming free black men as soldiers for the Union Army. Lowry later championed the establishment of the Pennsylvania Soldiers and Sailors Home. His farm on what was then Cooper Road eventually was sold to the Sisters of Mercy to establish Mercyhurst College.

Another former Maryland slave who landed in Erie was the aforementioned Hamilton Waters, who worked not only as a clothes presser at Vosburgh’s barber shop, but also served as a town crier and the city’s lamplighter. Waters was partially blind, the reason for which is unclear, but evidence suggests that while enslaved he was caught reading a book and punished accordingly. As he walked the streets lighting Erie’s gas lamps, Waters sang the old spirituals and plantation work songs of his youth. Accompanying him was grandson Harry Thacker Burleigh, who went on become one of the world’s great composers (see next section).

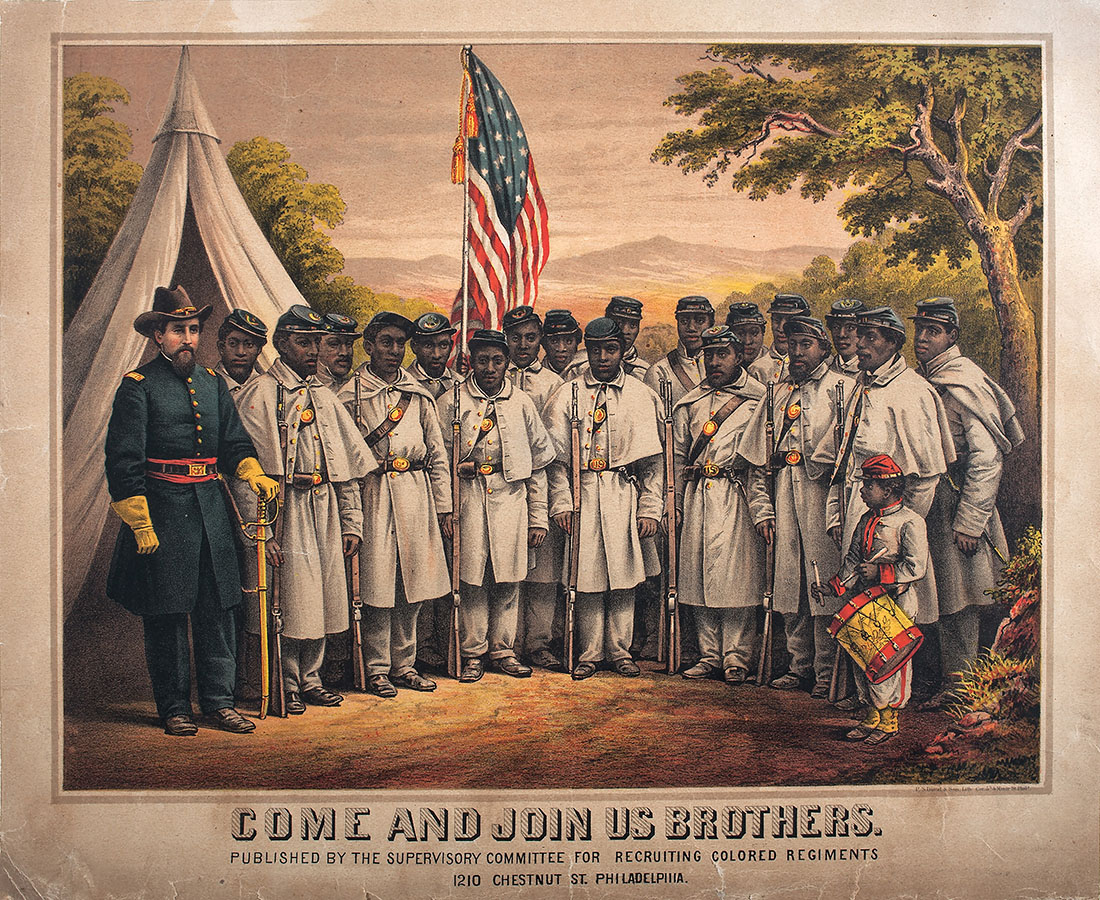

The terrible Civil War that had been coming on since the nation’s founding did not leave Erie untouched. Historical research is ongoing concerning the military service of African Americans from northwest Pennsylvania in both the army and navy. The 3rd United States Colored Regiment was organized August 1863 near Philadelphia, the first Pennsylvania unit of African American men.

Among the black men mustered in at Erie, Waterford or Meadville, we know the 43rd regiment of U.S. Colored Troops fought with great skill and courage during the 1864 Wilderness Campaign. That is underscored in this account of the Siege of Petersburg from the unit’s Chaplain, J. M. Mickley:

Colored non-commissioned officers fearlessly took the command after their officers had been killed or borne severely wounded from the field, and led on the attack to the close. . . .Here, on this, as on many other fields during this war, for the sacred cause of our republican liberties, free institutions, and the Union, the blood of the Anglo Saxon and the African mingled very freely in the full measure of devoted offering.

Sources

“Erie’s Underground Railroad,” Erie’s History and Memorabilia, April 1, 2017; at https://eriehistory.blogspot.com/2017/04/erie-underground-railroad.html; retrieved July 20, 2020.

“Morrow B. Lowry,” Pennsylvania State Senate; at https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/BiosHistory/MemBio.cfm?ID=4956&body=S, retrieved July 20, 2020.

Thompson, Sarah S., with additional research and an essay by Karen James. Journey From Jerusalem, 1795-1995 (Erie County Historical Society, 1996), pp. 11-27.

Image Sources

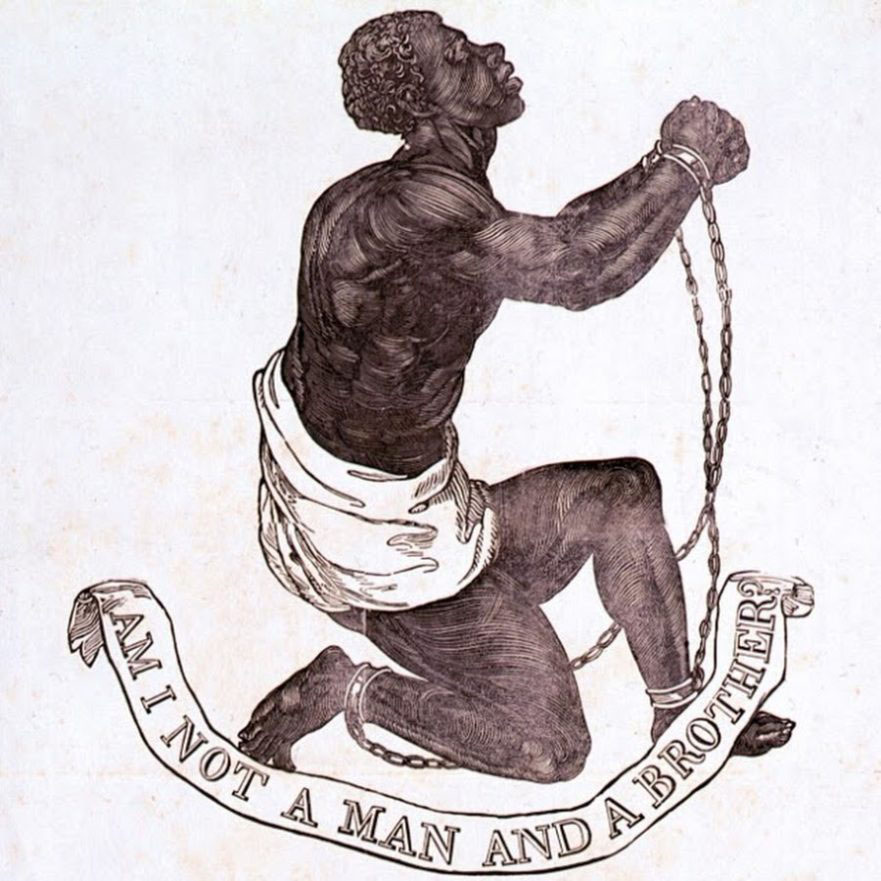

- Josiah Wedgewood, 1787 https://www.eternitynews.com.au/opinion/am-i-not-a-brother-or-sister/

- 1876, H.B. Robinson

- Photo by Chris Magoc, 2019

- Erie Maritime Museum website

- Image courtesy of Find a Grave: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7134179/william-himrod

- Illustration courtesy of the Harry T. Burleigh Society, and Jean Snyder’s superb book, Harry T Burleigh, From the Spirituals to the Harlem Renaissance (University of Illinois Press, 2016, p. 23)

- Illustration courtesy of Debbi Lyons’s richly illustrated and wonderful “Old Time Erie” site: https://oldtimeerie.blogspot.com/2013/01/wesleyville-me-church-and-underground.html?m=0

- Illustration from the Black Past (public domain): https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/1860-frederick-douglass-constitution-united-states-it-pro-slavery-or-anti-slavery/

- Illustration from the Pennsylvania State Senate: https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/BiosHistory/MemBio.cfm?ID=4956&body=S

- 1863 lithograph, Peters Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution: http://www.civilwar.si.edu/soldiering_join_us.html

*One of the most widely reproduced images of the abolition movement, this Josiah Wedgewood engraving dates to the founding of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in England. The question “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” is rhetorical to our modern sensibilities, while the black man on bended knee holds a complex set of meanings: is he a piteous supplicant pleading for his humanity to a dominant, presumably benevolent white society? Or is this the Christian archetypal appeal to moral conscience—a “taking the knee” prayerful entreaty that has continued, often with defiant courage, through the civil rights movement and now the Black Lives Matter Movement?