Fortified by one of the finest harbors on the Great Lakes, Erie enjoyed explosive growth in the last third of the nineteenth century, emerging as a major industrial and maritime city. Although African Americans comprised less than two percent of the city’s population, they established a growing network of religious, social, and fraternal organizations such as the “Colored Odd Fellows,” “Colored Republicans,” and the Bay City Lodge #68 of the Colored Masons.

No matter their color, the lives of poor and working-class people are always less well documented; they did not make it into early Erie County histories, nor publications such as The Men Who Made Erie (1888). But census records tell us that African Americans worked as janitors, teamsters, laborers, foundry workers, washerwomen, domestic maids, and clergy.

Others flourished as entrepreneurs. Among the most notable was local ice cream king John S. Hicks. The son of a Virginia enslaved man who purchased his freedom so he could marry a free woman, John S. Hicks found his way to Erie and became one of the most successful ice cream manufacturers and distributors in the state. At a three-story building on State Street he erected in 1892, Hicks produced 120 gallons every hour of fine ice cream from his own patented technology. Hicks shipped wholesale far and wide, while selling his ice cream from a first-floor parlor. As noted in Journey from Jerusalem, John Hicks, barber Albert Vosburgh, A.B. Bladen, and others in the prosperous black upper-middle-class were financial cornerstones of the larger black community, serving generously as lenders to those seeking to purchase property or otherwise find their way up.

John Hicks was not the only successful African American ice cream maker. Born into slavery in 1838 in Kentucky, James Franklin saw his mother sold out from under him and then ran away to Windsor, Canada in 1853. In 1866 he moved his family to Erie where he worked as a janitor for the Philadelphia & Erie Railroad Company’s office. By 1881 Franklin had begun manufacturing ice cream, and a decade later his success allowed him to buy a handsome brick home, the basement of which served as an ice cream factory.

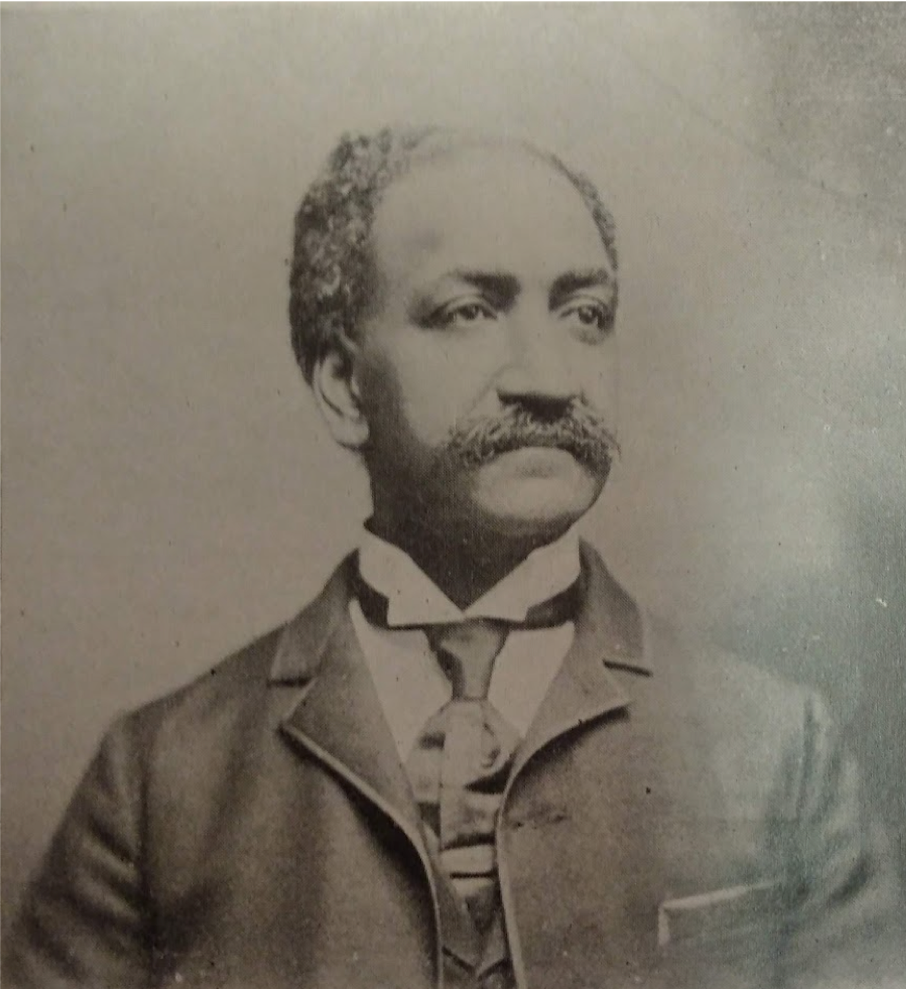

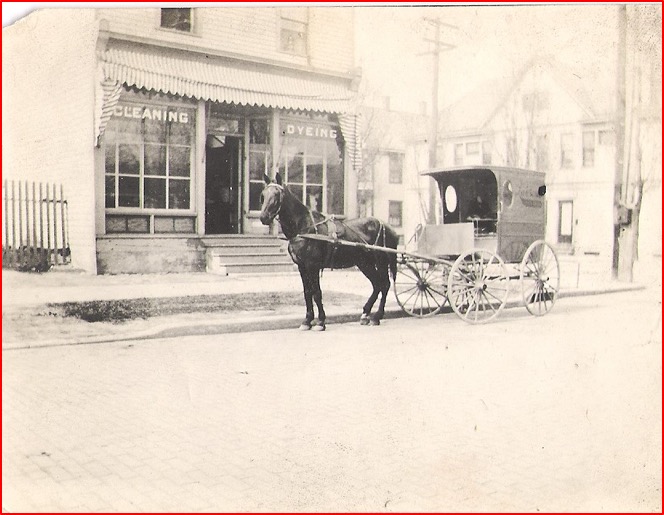

At the center of Erie’s African American community for nearly a century was the Lawrence Family. Descended from African and Native American parents, Lawrence matriarch Emma Gertrude Lawrence, came to Erie in 1881. After her husband’s passing, Emma was left to rear four young children. Taking in the laundry (much of it from adjacent “Millionaires’ Row” on West Sixth Street) to support her family, by 1906 Emma had founded Lawrence Cleaning and Dyeing—the first business operated by an African American woman in the city of Erie.

Emma’s involvement in civic organizations like the Red Cross and the YMCA seeded a legacy of vigorous work in and for the community by two generations of her descendants. Most notable was Earl Lawrence, an accomplished musician and arranger and gifted music educator. Earl established and played with various bands, performed in the Erie Philharmonic, and operated his own music studio from about 1916 until the Great Depression forced its closure. Master of more than a dozen instruments, Lawrence taught music to generations of students in the Fairview, Erie, Girard and Wattsburg school districts, while also serving on the faculty of the Erie Conservatory.

When Harry Burleigh returned to Erie, he stayed with Earl Lawrence. Burleigh helped to cultivate in Lawrence a belief in the power of music to help bridge social and cultural differences. Beyond his work with various African American churches and the Booker T. Washington Center, Lawrence performed with the local chapter of the Jewish human rights-centered organization B’nai Brith, as well as musical groups associated with some of Erie’s white ethnic communities.

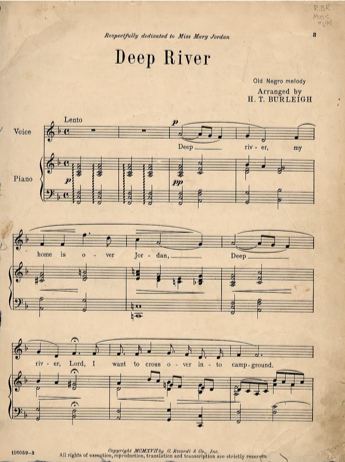

Overlapping with Lawrence’s extraordinary musical legacy was the emergence of Harry T. Burleigh as one of America’s great composers. Burleigh left Erie for New York City in 1892. Studying at the National Conservatory, Burleigh came to the attention of the brilliant Czech composer Antonin Dvořák—reportedly when Dvořák heard Burleigh singing old Negro spirituals while cleaning the Conservatory, a job he had taken to support himself. Dvořák was profoundly moved by the sound and encouraged Burleigh to integrate the music into his own compositions. “In the negro melodies of America,” he said, “I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music.”

Graduating from the National Conservatory in 1896, Burleigh became a member of its faculty and soon began more than a half-century career as the soloist at St. George’s Episcopal Church in New York City (missing just one performance in that time). With its white congregation resistant to hiring Burleigh, banker and industrialist J.P. Morgan cast the deciding vote in favor of Burleigh and his extraordinary baritone voice. Burleigh’s selection left a lasting schism in the congregation, with many of Morgan’s fellow financiers and industrial magnates leaving St. George’s permanently.

Soon thereafter, Harry Burleigh became the first African American soloist at Temple Emanu-El in New York City, a position he retained for 25 years. It was there that he conceived the arrangement of one of his most well-known spiritual works, “Deep River.” Burleigh went on to perform at prestigious venues throughout Europe, while his compositions and arrangements—inspired in the streets of Erie by his melodious grandfather Hamilton Waters—helped make him one of the most accomplished musicians of the century. It was rare to attend a classical music performance anywhere in America in these years and not hear a Burleigh composition.

Notwithstanding its great social and economic diversity, the African American community had long been held together by common threads—most importantly the Black church. Although it remains obscured by a lack of documentation, city maps from 1867 show a “Methodist Colored Church” at Third and Walnut, in the heart of Jerusalem.

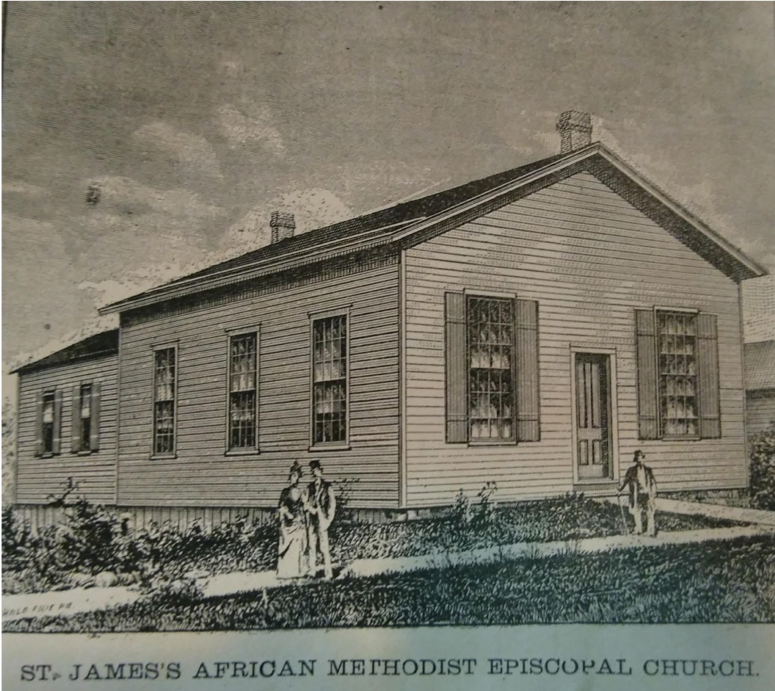

The oldest known African American congregation in the city is the St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in 1844 with roots extending to post-Revolutionary War Philadelphia. There, a growing black congregation at St. George Methodist Church were forcibly segregated from their fellow white congregants, driving young preacher Richard Allen to co-found the Free African Society in 1787. Soon Allen was preaching in a former blacksmith shop, and in 1816 he became the first bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Erie’s A.M.E. church was established in 1844 by Abraham Thomson Hall. Richard Allen’s legacy is memorialized in Erie with a large blacksmith’s anvil outside St. James.

St. James congregants met for a time in a modest wooden building gifted by the YMCA on East 6th (later moved to E. 7th) before eventually building the modern structure at 236 E. 11th Street. St. James’s place in Erie history was further elevated when it provided meeting quarters for the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1923.

Other churches came along, including Shiloh Baptist in 1915 and Trinity Church of God in Christ (1926), which settled in a building at 17th and Holland. In the 1920s the Marcus Garvey Movement and the so-called “Harlem Renaissance” (a renaissance mostly to white folks) summoned greater autonomy, cultural pride, and self-determination for African Americans throughout the nation. It was in that wider context that Erie witnessed the difficult split of black congregants from white-dominant St. Paul Episcopal. Coming not without dissension, the formation of the short-lived “Mission Sunday School” was driven partly by the arrival of African Americans from the strictly segregated South where the black church had long served as a sacred refuge from white oppression.

Like most cities in America, what is known of Erie’s early race relations is both thin and somewhat contradictory. Schools appear to have been largely integrated. It was in fact a notable affront to the hopeful promise of freedom for which the Civil War was being fought when in 1862 Frederick Douglas reported an effort “to have the colored children [of Erie] . . . taught in separate schools from white children.” African American parents challenged that “indignity, declaring that their children were as good as those of the whites, and no distinction should be made on account of color.”

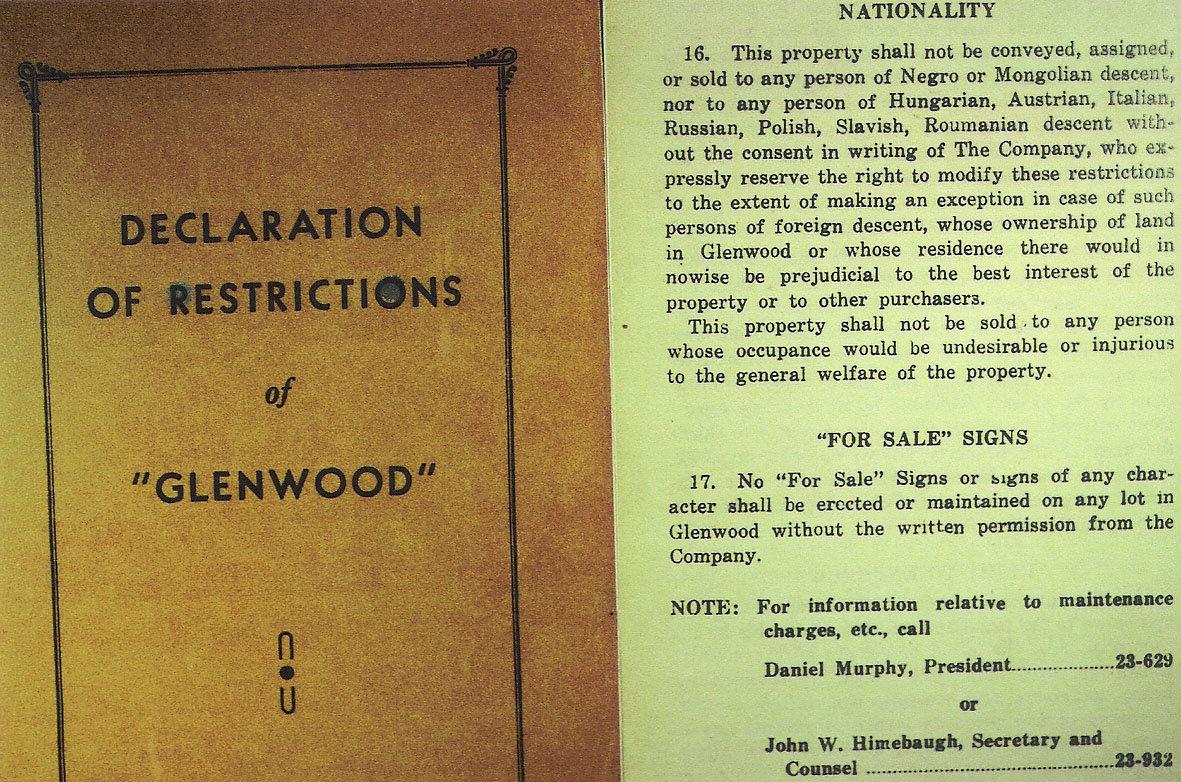

Also integrated (at least as the record indicates) were most businesses and churches, and GAR posts for Civil War veterans. Legal or formally organized restrictions on housing such as covenants and redlining practices that became common after WWII were rare. It appears that housing was restricted more by income than race—at least until the 1920s, when Glenwood and other newly emerging suburban communities made racial exclusion explicit.

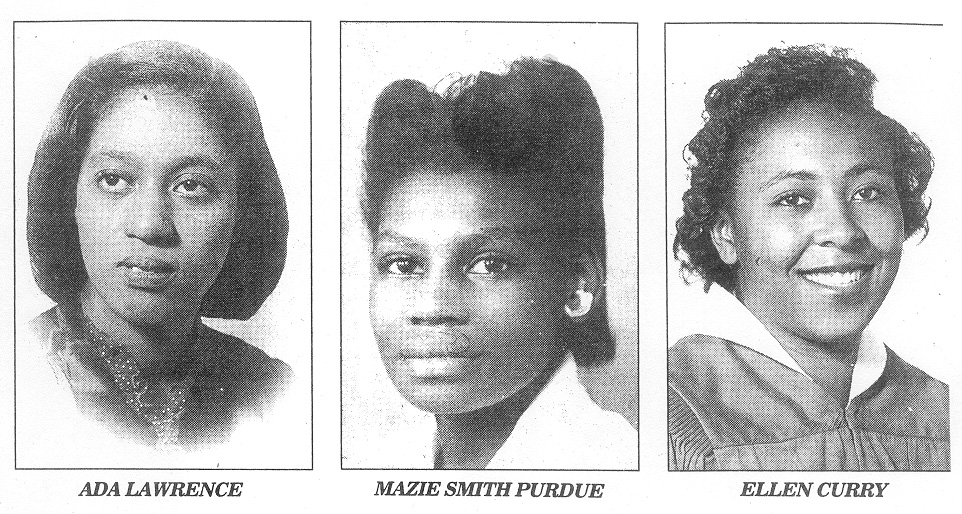

Underneath this generally benign history of race relations is another story that becomes clear in the historical record of the mid-20th century. Ellen Curry, Ada Lawrence, and Mazie Smith Purdue recall decades when an African American “could shop on State Street all day long, but there was no place you could sit and have a cup of coffee or a sandwich because of the color of your skin.” They never discussed this “embarrassing secret” with white friends, “only to each other.”

Further, some local schools had unwritten rules that denied extra-curricular activities and school-to-work programs to African American high school students. For decades, Erie nursing schools did not accept African Americans, companies explicitly told applicants that they did not hire black people. Earl Lawrence’s band performed at the Kahwka Club, but as a black man he could not join the elite social organization. African American soldiers from Erie who served in the Spanish-American War and World War I served in segregated units, performing menial jobs, while black drum and bugle corps units always marched in the rear in public parades down State Street.

Founded in 1923 on West Third Street in Jerusalem, the Booker T. Washington Center fielded occasional complaints of racial discrimination at General Electric. Otherwise in its early years, the Center focused on the improvement of public health, education, and recreational opportunities for the community. A few years earlier, Jessie Pope had led the founding and first years of the local NAACP chapter. Soon Jesse Thompson became president, leading the organization as it became the foremost advocate for civil rights in the region.

In the years preceding the NAACP on January 15, 1907, the Erie Daily Times ran a story about a formal protest against the public staging of “The Clansman” at the Majestic Theatre. “The Clansman,” a racist retelling of the Civil War and Reconstruction by Thomas Dixon Jr., served as the inspiration for Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith’s epic 1915 film that drove the rebirth of the modern Ku Klux Klan. The Klan of the 1920s boasted a national membership of nearly five million and had particular strength in western Pennsylvania, including Erie County. At the 1926 “klorero” of the state Klan, Reverend Herbert C. Shaw of Erie was elected Grand Dragon. Reflecting and reinforcing a national tide of racist xenophobia directed against African and Mexican Americans, immigrants, Catholics, and Jews, the Klan was instrumental in advancing passage of the nativist National Origins Act of 1924.

Sources

Jenkins, Philip, “The Ku Klux Klan in Pennsylvania, 1920-1940.” Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine v. 62, n. 2 (April 1986): 120-137; at file:///Users/cmagoc/Downloads/3998-Article%20Text-3843-2-10-20151027-1.pdf, retrieved July 20, 2020.

Loucks, Emerson Hunsberger. The Ku Klux Klan in Pennsylvania: A Study in Nativism (New York-Harrisburg: The Telegraph Press, 1936).

Beckerman, Michael Brim. New Worlds of Dvořák: Searching in America for the Composer’s Inner Life (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003).

Thompson, Sarah S., with additional research and an essay by Karen James. Journey From Jerusalem, 1795-1995 (Erie County Historical Society, 1996), pp. 28-49.

Wright, Richard R. The Centennial Encyclopedia of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (Philadelphia, 1916); at https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/wright/wright.html, retrieved July 20, 2020.

Image Sources

- Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Historic American Sheet Music, Duke University: https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/scriptorium/sheetmusic/n/n06/n0694/n0694-3-150dpi.html

- Erie Illustrated (1888)

- N/A

- Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- Johnny Johnson, The Lawrence Family Archives

- –